Many Americans think the H‑1B visa program was created to help employers fill genuine gaps in the labor market with highly skilled foreign professionals. Sadly, that is not only false, but it was never the intention.

The H-1B Visa was deliberately designed by lobbyists who worked with Congress to undercut American workers: displacement of American workers was a feature built into the system, not an unintended consequence.

If you were on X (formerly Twitter) and participated in “The Great H‑1B Christmas” kerfuffle of 2024, you may recall viral screenshots of employers like Panda Express filing H‑1B visas for managerial positions. Those posts pulled data from a little-known but critically important document at the heart of the program: the Labor Condition Application, or LCA.

What is a Labor Condition Application?

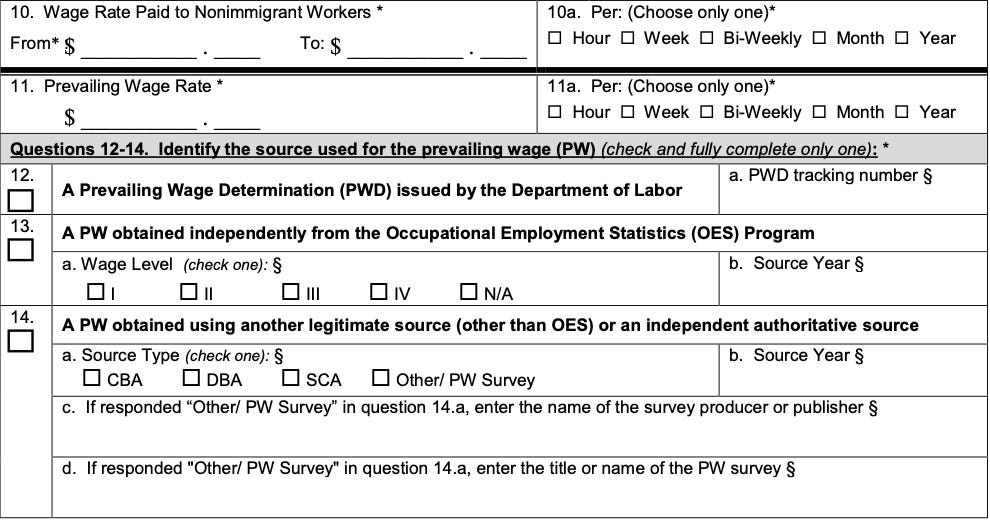

An LCA is a short form that employers must file with the Department of Labor before they can hire an H‑1B worker. In the LCA, employers attest to the validity of requirements for the job, such as the occupation title, work location, and the “prevailing wage” (the wage they agree to pay), along with a promise that hiring a foreign worker won’t negatively affect similarly employed U.S. workers.

The attestation required in the LCA was supposed to be a safeguard that would prevent local wages from being depressed by foreign workers. However, it’s a rubber‑stamp process with virtually no scrutiny that allows employers to harm American workers by bringing in cheaper foreign labor, all while giving them plausible deniability of wrongdoing.

Worse still, the entire LCA system runs on an honor system: employers themselves select and report the prevailing wage they claim to pay. In practice, this lets them game the process and legally undercut American wages — exactly what the safeguard was meant to prevent.

I’m writing this Substack to help policymakers and legislators see exactly how the current prevailing wage rules don’t work in the best interests of American workers.

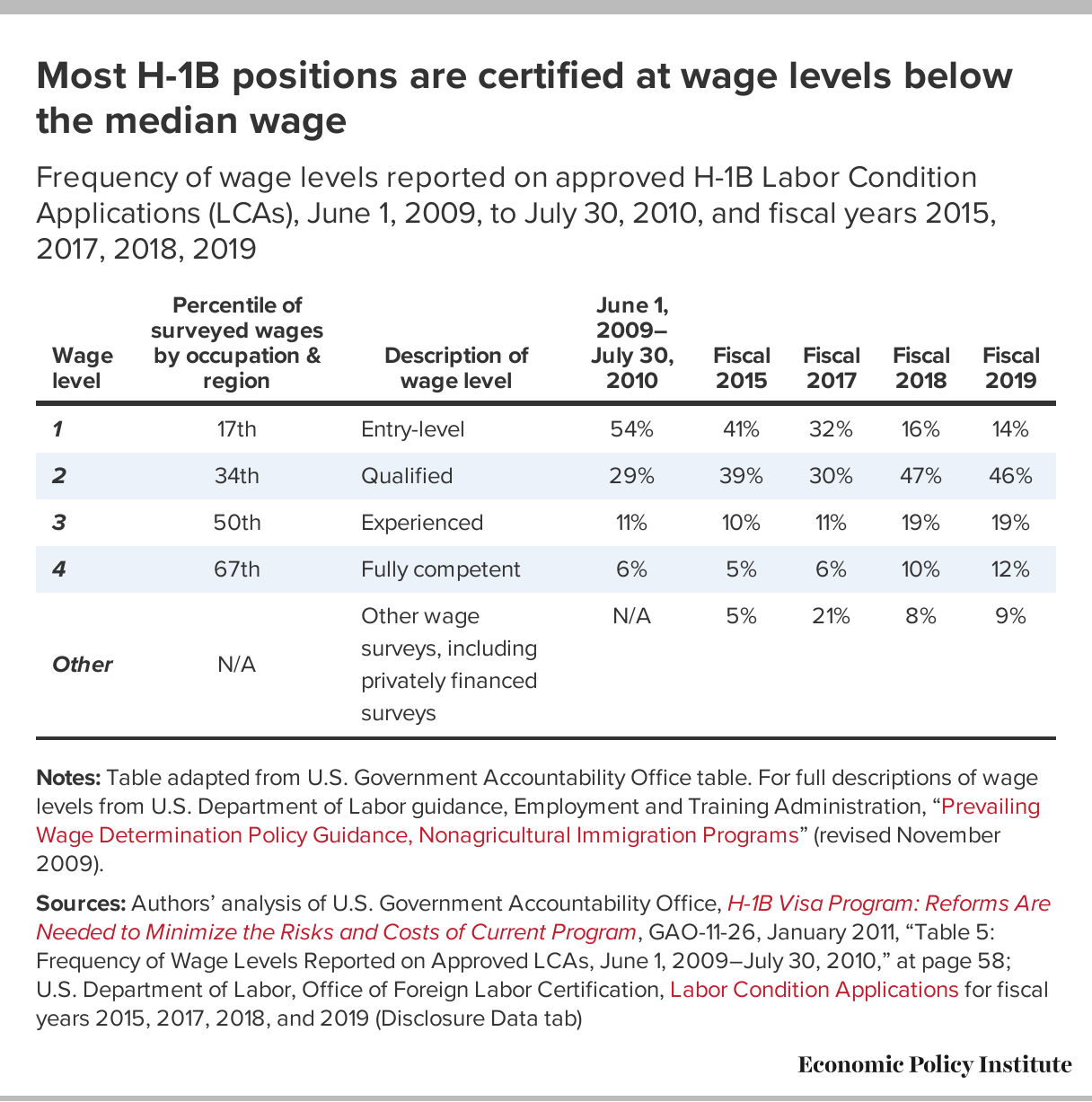

The Department of Labor (DOL) publishes wage data for thousands of occupations, divided into four prevailing wage levels: Level I through Level IV.

Level I (the lowest salary tier) is meant for genuinely entry-level roles requiring only basic skills and close supervision, typically set near the 17th percentile of wages for that job. Level IV, the highest, is meant for senior specialists and leaders.

In theory, an employer would select an appropriate wage level that reflects the actual level of technical skills, real-world experience, credentials, and responsibilities for the role they want the foreign worker to fill. In practice, employers can and do simply classify positions as entry-level, even when the roles plainly require experience and specialized skills.

This begs the question: if the goal is to bring in highly skilled workers to supplement American workers, why are 60% of all LCA applications asking for foreign workers in the Level I and Level II categories?

Wage categories are not the only way employers game the system.

One issue is that employers can choose broader or cheaper occupational codes. For instance, labeling a data scientist as a generic “analyst” allows them to claim a lower prevailing wage. They can also list the job location in a cheaper labor market, even if the work is really performed in a high-cost city. This is a common tactic among large Indian IT outsourcing companies that place workers at client sites in expensive metro areas.

Hear from two young American STEM workers who cannot find work despite their experience and credentials - “A lot of these jobs too will ask for someone with five years of experience but then they are paying at entry level slaries.” With a population estimate of 659,305 H-1Bs in the job market (not to mention 547,404 foreign students here on work authorizations), It’s not AI taking their jobs.

Lastly, they can submit private wage surveys that, unlike the government’s own data, often show suspiciously low pay, especially when funded or selected by the employers themselves.

The result? Many H‑1B workers legally earn far below what an equally qualified American worker in the same city would make.

The above aren’t loopholes. It is how Congress wrote the law.

The DOL has only seven days to certify an LCA, and the sheer volume prevents them from taking the time to scrutinize the form to ensure, among other things, the job truly requires advanced skills. Or, whether the wage level chosen matches actual responsibilities. Moreover, the department can only open an investigation after a formal complaint is filed or if the employer is already labeled a willful violator. Even then, the punishment is a fine, not a cancellation of the visa.

The LCA process at its best is a compliance theater that results in bringing in ordinary workers performing routine tasks, not cutting-edge specialists the public has been sold on. And with limited oversight, there’s almost nothing that can be done to root out the bad actors.

Policy Solutions

Congress alone can fix the deepest flaws. But the executive branch isn’t powerless—especially through rulemaking under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), which, if grounded in evidence, can withstand any and all legal challenges.

One bold, targeted reform would be to significantly raise the required wage level. Instead of allowing employers to pay at the 17th or 34th percentile, the Department of Labor could set the minimum required wage closer to the 75th percentile of the local market rate. After all, if employers truly need to look overseas to fill a role because no qualified Americans are available, that role should be compensated like the scarce, high-demand position it’s claimed to be.

Beyond that, the DOL should:

Tighten the criteria for private wage surveys, allowing only recent, statistically valid, and publicly available surveys—eliminating cherry-picked or employer-funded studies.

Require detailed documentation showing why a specific wage level and occupational code accurately reflect the role’s duties.

Ensure wages match the actual work location, preventing employers from listing low-cost regions to cut pay.

Make all LCAs, wage determinations, and justifications fully transparent and searchable online, allowing public oversight.

By using the APA rulemaking process, which includes notice, comment, and a robust administrative record, the government can base these changes on clear economic evidence and congressional intent to protect U.S. wages. This approach makes it far harder for courts to strike them down as “arbitrary and capricious.”

Such reforms wouldn’t stop every misuse. But they would force the program back toward what it was sold to us as—a limited channel for hiring truly exceptional foreign talent, not a subsidy to replace American workers with cheaper labor.

At its heart, the LCA process is a case study in regulatory capture. It was built, from the start, to be fast, predictable, and employer-friendly, all at the expense of American workers. Bringing real accountability and market fairness back into the system shouldn’t be controversial. It should be the minimum Americans can expect from an administration that PUTS AMERICANS FIRST.

Conclusion

In closing, the next time you hear immigration lawyers or H‑1B advocates insist these visas can’t possibly be used as cheap labor while smugly citing the statute that says employers must pay the higher of the actual wage or the “prevailing wage” (8 U.S.C. § 1182(n)(1)(A)), you now have all the information you need to counter them. You now know how the system really works.

This was a well written article.

Excellent article. Thank you very much!