Doctors Gambled on a Career in Medicine – Some Lost Big!

Two Weeks Later, American-Trained Physicians Remain Locked Out of the System

It’s been over two weeks since Match Day 2025, which occurs each year, usually around mid-March, and comes at the end of Match Week. At the beginning of Match Week, medical students find out if they have matched into a residency program, and at the end of the week comes national Match Day, when they find out where exactly they have matched.

Across the country, those who matched are preparing to relocate, sign contracts, and begin the final phase of their training.

But for thousands of American-trained doctors, there are no next steps to licensure and the practice of medicine. For them, there is no welcome letter, no residency, and no path forward. This is because they didn’t match!

To be clear, if a medical doctor does not receive a residency after graduation, they will never obtain a license to practice medicine.

The System Continues to Eat Its Own

The Match is the national placement system run by the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP). It pairs medical graduates with residency programs using a computerized algorithm based on mutual preferences. It works in lockstep with the Association of American Medical Colleges’ (AAMC) Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS). After applicants have submitted their applications through ERAS and have had the opportunity to interview, the NRMP handles the matching process.

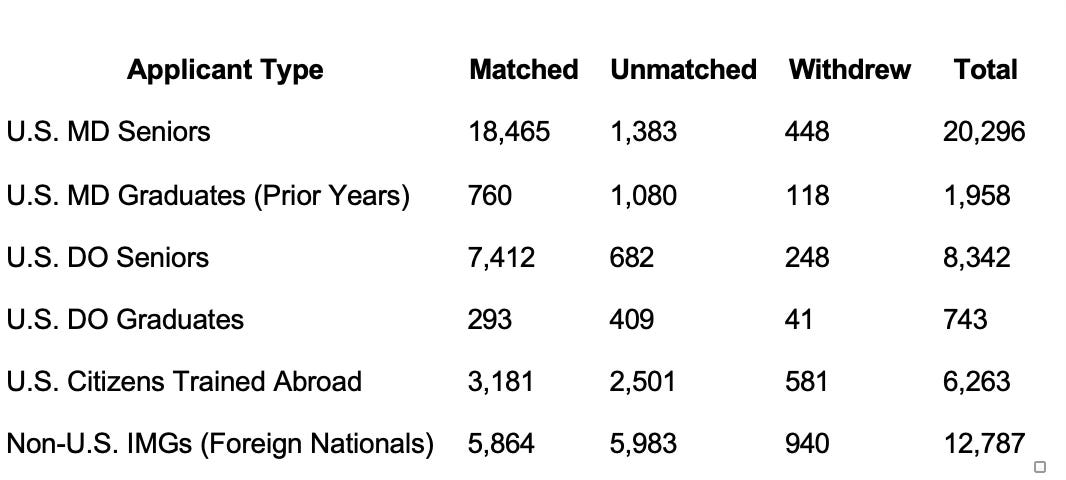

The NRMP has become a critical component in the process when it comes to being a licensed physician in the US. In 2025, more than 50,000 people applied for residency positions. And despite one’s best efforts, the results are far from guaranteed.

Over 6,000 American-trained doctors — including U.S. MDs, DOs, and U.S. citizens who studied abroad — did not match.

Meanwhile, nearly 6,000 non-U.S. citizen foreign-trained physicians (FTP) were placed in U.S. residency positions — many of which are funded by Medicare, using taxpayer dollars.

Things have only gotten worse since we began studying and reporting on this crisis. For instance, in 2021, 4,356 FTPs were matched to residencies at US teaching hospitals, and in 2025, that number increased to 5,864.

As unmatched physician Dr. Doug Medina told us six years ago in the below interview, the debt doesn’t disappear—even if the dream is stalled.

Interview with Dr. Doug Medina

Many unmatched doctors carry between $200,000 and $400,000 in medical school debt.

They’ve done everything the system asked of them — years of school, board exams, clinical rotations — only to be left with no license, job, or clear path forward.

Some will try again next year. Others will leave medicine entirely, despite the time, effort, and money invested.

A Benign Monopoly?

The NRMP's position as a virtual monopoly in residency placement, despite its 2004 antitrust exemption, raises questions about accountability and fairness. Without meaningful competition or oversight, programs face limited pressure to address bias in their selection processes.

Moreover, serious questions have arisen that indicate institutional patterns of preference: multiple layers of subjectivity that include unstructured interviews that lead to conscious and unconscious prejudices, variable interpretation of international credentials, informal networks that influence who is matched into programs, and discretionary application filters that may screen out certain groups.

In the end, we trained these doctors. We let them drown.

The House Wins and You Lose

This is not a personal failure. It’s systemic neglect, and the cards are stacked against our doctors.

Given the unmatched rate has been consistent over the years, it is as if the system has figured out an optimal percentage of “breakage” that will permit it to continue the status quo without increasing the number of medical schools or residency positions.

Moreover, august bodies such as the American Medical Association (AMA) and AAMC are largely silent when it comes to the unmatched issue, and the advice they offer is feckless. The AMA recommends getting a job in a “clinical setting” or trying a “new approach” that includes “deconstructing” everything they may have done wrong in the application process. Perhaps the AMA and AAMC could offer a program that provides medical malpractice insurance to unmatched doctors so they could practice under supervision while waiting for the next chance at the roulette wheel.

The Cost of Monopoly

Taxpayer-Funded Training — But Not for Americans?

Residency positions are primarily funded through Medicare, meaning American taxpayers are footing the bill. This is an investment Americans are happy to make in the current and future generations to ensure the best possible health outcomes.

However, since 1997, Congress has placed a cap on how many residencies each hospital can fund through Medicare. That cap has not kept pace with the growth in U.S. medical graduates or even the general population, and it does not require that hospitals prioritize American citizens or American-trained doctors.

So, every year, thousands of American graduates are left without jobs, while foreign nationals are placed into U.S. training programs.

These unmatched doctors are not unqualified. They studied here in the US. They passed the exams. They are ready to serve.

The Path to Recovery

Three years ago, I testified before the Immigration and Citizenship Subcommittee on the issue of FTPs and residencies. I informed the committee that we do not have a doctor shortage in America. The demand to go to medical school is higher than ever. For instance, on average the acceptance rate to a medical school is 40% and 5% at the most competitive schools. The interest in attending nursing programs is equally high.

The path to a fair medical residency matching process requires the following changes:

1) Medical schools should be increased.

2) Residency programs be increased.

3) American citizens and lawful permanent residents are prioritized in the Match.

4) Acknowledge biases exist while working systematically to address them. For instance, why does one program seem to accept FTPs from a specific country?

5) Initial application reviews be anonymous.

6) Evaluation rubrics should be more structured.

7) Evaluation metrics should be standardized.

8) Match outcomes for FTPs should be audited.

Only through continued scrutiny and reform can the system better serve its essential role in medical education while ensuring fair opportunities for all qualified candidates.

We do not have a doctor shortage crisis—we have a gatekeeping crisis! And the gatekeeping is impacting health outcomes for all Americans.

In closing, if you are reading this and you are unmatched or know someone who didn’t match reach out to doctors that who organizing like those at unmatchedmd.com and visit our Doctors Without Jobs page and introduce yourself.

P.S. If you are curious as to how Canada and the rest of the world prioritize their doctors when it comes to residency training, click on the below link:

https://ifspp.substack.com/p/training-canadian-doctors-for-canada

I agree that we should be granting residencies to American citizens as a high priority. I analyzed the statistics on your spreadsheet. In 2025, 91% of US M.D. Seniors were matched followed by 88.9% of U.S. D.O. Seniors. All other categories show considerably lower percentages.

FWIW, the real tragedy is the much lower percentages of American citizen science and engineering Ph.D.s that end up with a career in science only a decade after earning their doctorate. Ph.D.; programs take longer than completing medical doctor programs. My impression is the percentages there are about 25%. See the April 14, 1993 Wall Street Journal article by G. Pascal Zachary, "Black Hole Opens in Scientist Job Rolls." This article is no longer available. Please request a copy by sending me an email to government [at] CGNP [dot] org.